I used to love inspirational quotes. Yes, it’s true, I was one of “those people” – the endlessly inspired, the Pinterest-addicted, the posting-uncredited-sunsets-slapped-with-an-inspirational-quote-on-Facebook.

I collected them, copy-pasting them haphazardly into a Word document labelled “Quotes” – simple and sweet. I did this… because. I liked the feeling of reading a well-written phrase and going – “yes, that’s me!”, or finding an obscure term that gave me artsy vibes. Not that I ever did anything more than that. It never inspired action, per say (to seize the day, to love yourself, to follow your dreams) – at most, it inspired some lackluster Tumblr posts.

To the credit of my teenage self, I did include the name of the (alleged) author and the (alleged) definition – but never checked if it was correctly attributed, or if there was any shift in its meaning once divorced from the context. And whilst it doesn’t sound like the worst crime pertaining to intellectual property that there is, I did get quite burned when a half-formed thought of a tattoo led me to do more research.

The tattoo idea? The word “drapetomania”, defined as “an overwhelming urge to run away”.

The inspiration? Such a lovely, pretty word, on the border of scientific and artistic, perfectly tailored to my teenage angst and struggling identity.

The actual context?

...

Pseudo-scientific racism.

Drapetomania was a conjectural mental illness that, in 1851, American physician Samuel A. Cartwright hypothesized as the cause of enslaved Africans fleeing captivity. Contemporarily reprinted in the South, Cartwright's article was widely mocked and satirized in the northern United States. The concept has since been debunked as pseudoscience and shown to be part of the edifice of scientific racism. The term derives from the Greek δραπέτης (drapetes, "a runaway [slave]") and μανία (mania, "madness, frenzy"). As late as 1914, the third edition of Thomas Lathrop Stedman's Practical Medical Dictionary included an entry for drapetomania, defined as "Vagabondage, dromomania; an uncontrollable or insane impulsion to wander." (Source: Wikipedia)

... Yikes. (I never got that tattoo). And that was my first introduction to the pitfalls of the instant gratification of devouring contextless art, and in that moment, my younger self decided – no, I am not going to be that person that shares racist memes and propagates the type of ignorance that comes with valuing aesthetics over context. I – personally, I – wanted to know better and be better. I didn’t care about “reclaiming words”, especially words I had no stakes in; didn’t care if it was “derived from Greek”, or “it made sense at the time”, or whatever nonsense people come up with when they’re confronted with their own ignorance. Words cannot be redeemed overnight just because it would be prettier against the backdrop of a rainforest in a square Pinterest post but only as long as we’re not making anyone uncomfortable by pointing out the unfortunate historical implications. Perhaps in the grand scheme of things this is a trivial matter. But – imagine getting a tattoo of that. And this is the story of how I became a killjoy that doesn’t believe in the veracity of inspirational quotes unless I can track it down to the source. So welcome… to Hunting Inspiration, a series where I track down the origins of a quote purely out of spite.

"From my rotting body, flowers shall grow and I am in them and that is eternity."

Edvard Munch (allegedly)

Edvard Munch - Self-portrait with a Bottle of Wine (1930). Based on an earlier 1906 portrait, this version was made following his stay in a recovery hospital after his mental collapse in 1908

I cannot tell you where I first read this particular quote, but I can tell you it was likely when I was going through my Expressionist phase as a troubled youth, in the same manner other people went through emo phases. Death to the Romantics! – I cried, as I wrote art analysis on Munch’s The Scream and fervently gazed into the abyss of Francis Bacon’s screaming popes. I was full of pretentious artistic fervour at the tender age of fourteen.

Allow me to give more insight on the artist in question. Edvard Munch was a Norwegian painter who lived from 1863 to 1944. His best known work is indeed The Scream (which you would absolutely recognise), but his art portfolio covers a vast array of angst and sickness, of death and heartbreak. He was rather genre-less in some aspects, though most theorists class him within at least Expressionism and Symbolism.

The quote itself is rather dark, and rather macabre, and rather everything I aspired to be artistically at a young age. In its current (alleged) form, it feels profound, something he might have written while bedridden and pondering over the legacy he would leave behind. This is not that much of a stretch, considering he was very sickly as a child, and watched as both his mother and sister died of tuberculosis, eventually succumbing to his own illness. I got very curious over where this quote might have come from – a biography, a critique, perhaps a letter? And so, I began my hunt.

As with any important projects in life, I started with a simple Google search:

Screenshot showing the first page of Google results

From the first page of results, three out of the first four results direct you to quotation websites. Do note the second link to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention article from 2011 written on Munch’s relationship with disease and illness. As you do, one supposes, and despite being a very interesting article, it offered no clue as to the original source of the quote, despite having seven other sources in its bibliography.

Just further goes to prove how we take inspirational quotes to face value when we would otherwise investigate them with academic rigor.

Goodreads and Brainyquote offer no sources, to no one’s surprise, so I take a look at Wikiquote, who has proven reliable – at times. And here it is in all its glory, Wikiquote listing the source for this quote.

Screenshot showing Wikiquote's source for this quote

Huh.

Cover of Sustainable Landscape Construction: A Guide to Green Building Outdoors (2007)

In case you might think I pasted the wrong screenshot, or that your eyes might be suddenly playing tricks on you, allow me confirm the Wikiquote source:

Quote in Sustainable Landscape Construction: A Guide to Green Building Outdoors (2007) by William Thompson and Kim Sorvig, p. 30

My initial reaction upon reading this may or may not have been a high-pitched exclamation of “sustainable landscape construction!!!” – but you have no proof. But seriously – what in the world is an expressionist painter, whose art is riddled with death, disease and anguish… doing in a book about landscaping?

Edvard Munch quote in Sustainable Landscape Construction

Now this is a rabbit hole I couldn’t stay away from. After some sleuthing around, I managed to find a copy of the book (in all its 412-page glory), and found the Munch quote on page 30:

It reads:

“Frightening as bodily decay is to many people, we are part of that cycle. Some individuals and cultures have celebrated this: the painter Edvard Munch wrote, “From my rotting body, flowers shall grow and I am in them and that is eternity.”[80] Green cemeteries return to simple, un-embalmed burial in wood caskets or even shrouds.”

Perhaps I was a too hasty in thinking sustainable landscape construction had nothing to do with death, but I didn’t expect this talk of cemeteries. Truly a sign that landscaping is a lot more goth that people give it credit for.

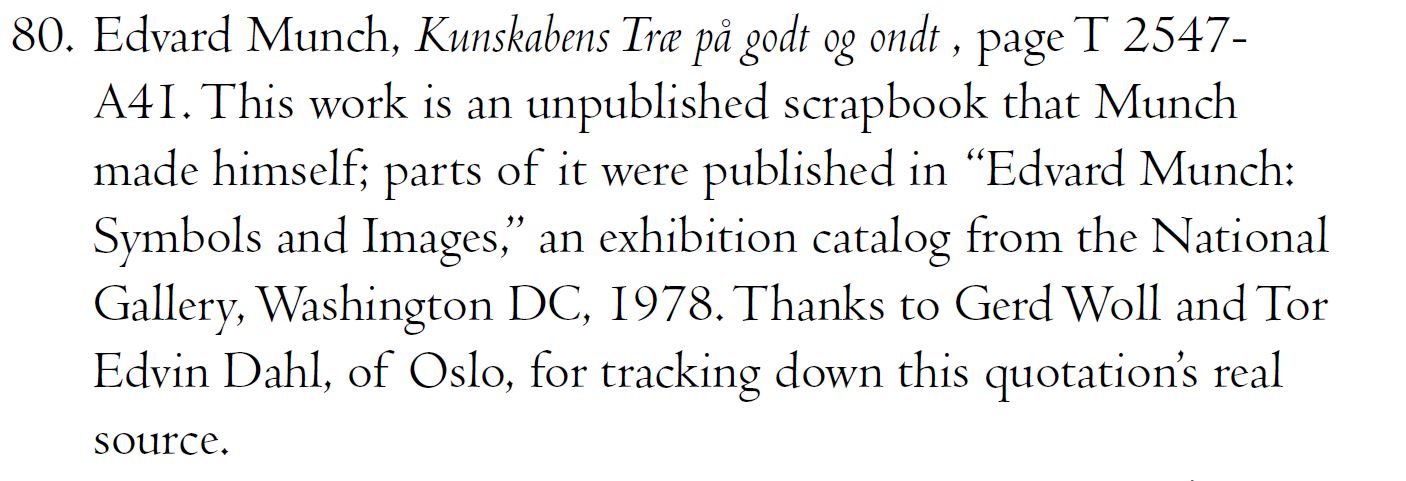

Reference 80 in Sustainable Landscape Construction

Down we scroll to reference no. 80. It reads:

“80. Edvard Munch, Kunskabens Træ på godt og ondt , page T 2547- A41. This work is an unpublished scrapbook that Munch made himself; parts of it were published in “Edvard Munch: Symbols and Images,” an exhibition catalog from the National Gallery, Washington DC, 1978. Thanks to Gerd Woll and Tor Edvin Dahl, of Oslo, for tracking down this quotation’s real source.”

It is absolutely hilarious to me that the author is thanking Woll and Dahl for tracking down the original source, while Wikiquote still lists their own landscaping book as the original source. And we keep going down the rabbit hole it seems!

But things are getting a bit more interesting. So if this quote was originally part of an unpublished scrapbook, then it would make it almost impossible to track the exact piece of paper it was written down… right?

In any case, we have another lead. Let’s search for Kunskabens Træ på godt og ondt and see what we find.

Screenshot of the first page of Google results for Kunskabens Træ på godt og ondt

Norwegian. Norwegian is what we find, and I feel a little silly now for not expecting this.

After a quick foray to Google Translate, we learn that Kunskabens Træ på godt og ondt is Norwegian for “The Tree of Knowledge for Good and Evil” (but not before Google Translate condescendingly suggests we correct Kunskabens to Kundskabens (with an extra d); this might come in handy if we’re foraging for Norwegian search terms. Very biblical – very artsy.

At this point, I realise there might be a stronger lead in the landscaping book than this Norwegian tree, and that is the exhibition catalog Edvard Munch: Symbols and Images. The reference states that only part of the unpublished scrapbook was included in this catalog, but wouldn’t it be great if the very part we are looking for was in the catalog? Worth a try, even though a 1978 catalog doesn’t inspire great faith in having it archived on the Internet.

Screenshot of Edvard Munch: Symbols and Images catalog on the DC National Gallery website

To my utter surprise, the entire catalog is archived on the DC National Gallery website!

And even better, they provide access to a free downloadable pdf, without faffing about with paywalls or 404 pages. Victory for the free digitalisation of knowledge!

Edvard Munch: Symbols and Images is a collection of essays pertaining to various artistic aspects of Munch’s work, and it was originally published in 1978, standing at 274 pages, 10 essays, and several reference pages. As lovely an evening it would make to read essays from the seventies on expressionist art (this is not sarcasm!), I’m a woman on a mission who knows how to use the search function in a pdf.

“Kunskabens” provides no matches. Infuriatingly enough, neither does “Kundskabens” (with an extra d), and I blame Google for my misery. After further frantic Googling, I find that some websites list this scrapbook as “Kunskapens” (no d, but with a p instead of a b). And finally, this search presents me with two matches. Thank you Google (but also damn you, since you’re the one who gave me the wrong translation in the first place!)

Word search "Kunskapens" in Edvard Munch: Symbols and Images

It reads:

43. Munch-museet, ms. T 2547. The content is similar to that of other texts written c. 1893-1894, although as cited here derives from Munch’s portfolio of graphics now entitled “Kunskapens trae pâ godt og ondt” and probably written during the late teens and twenties.(...)

66. Munch-museet, ms. T2547 (“Kunskapens trae pâ godt og ondt”), compare note 43

Here, our friend Kunsk-something refers to a portfolio of graphics rather than an unpublished scrapbook, and references no. 43 and 66 are both linked to the essay Love as a Series of Paintings and a Matter of Life and Death by Reinhold Heller.

So let’s jump right to these references inside the essay:

Reference 43 in Edvard Munch: Symbols and Images

Reference 43 reads:

The new mysticism ultimately discovered by him, as by the Schwarze Ferkel writers, was the one means by which a deterministically and materialistically oriented mentality seemed still to permit a sense of immortality: sex. Through sex, through the mingling of male sperm and female ovum, new life could be generated by already existing life, thereby guaranteeing the continuation of life so that “the chain binding the thousand dead generations to the thousand generations to come is linked together,” and “new life shakes the hand of death.”43 In the processes of love and human reproduction, death was deprived of its sting and its victory.

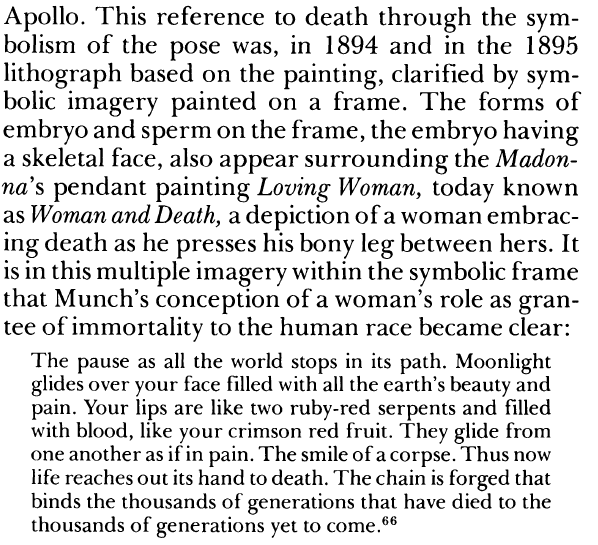

Reference 66 in Edvard Munch: Symbols and Images

And reference 66 reads:

This reference to death through the symbolism of the pose was, in 1894 and in the 1895 lithograph based on the painting, clarified by symbolic imagery painted on a frame. The forms of embryo and sperm on the frame, the embryo having a skeletal face, also appear surrounding the Madonna’s pendant painting Loving Woman, today known as Woman and Death, a depiction of a woman embracing death as he presses his bony leg between hers. It is in this multiple imagery within the symbolic frame that Munch’s conception of a woman’s role as grantee of immortality to the human race became clear:

The pause as all the world stops in its path. Moonlight glides over your face filled with all the earth’s beauty and pain. Your lips are like two ruby-red serpents and filled with blood, like your crimson red fruit. They glide from one another as if in pain. The smile of a corpse. Thus now life reaches out its hand to death. The chain is forged that binds the thousands of generations that have died to the thousands of generations yet to come.66

This is all very interesting, but it doesn’t explain the “rotting body” quote, and I’m not satisfied to be told that it’s found in an unpublished scrapbook; I want more details to verify the original context. So I start looking up random words from the quote, and start getting frustrated at the maddening amount of references to “rotting” and “flowers” in this pdf. This quote appears verbatim in multiple parts of the book, but there are other hints of it in other sections.

For example, the essay The Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil by Gerd Woll:

Word search "rotting" in Edvard Munch: Symbols and Images

It reads:

The earliest written indications of the fact that Munch regarded life eternal to have become actuality through transubstantiation are found in a couple of notes from 1892, which probably refer to an experience in Paris a few years earlier:

“I was walking up on the heights enjoying the soft air and the sun—The sun was warm and only once in a while some cool puffs—as if from a deep cellar. The moist earth was steaming—there was a smell of rotting leaves—and how quiet it was around me—and still I felt how things were in ferment and lived—in this steaming earth with the rotting leaves—in these bare branches that were soon again to sprout and live and the sun was to shine on the green leaves and flowers—and the wind was to bend them.

I felt it to be a rapture to pass into, be united with— become this earth which always, always fermented, always shone upon by the sun—and lived, lived—and there were to grow plants up and out of my rotting body—and trees and flowers and the sun were to warm them and I was to be in them and nothing was to come to an end—that is eternity.”

A reference to this theme is found in the text written on a small card placed in the volume (see text in “Tree of Knowledge” between p. 60 and p. A 41).

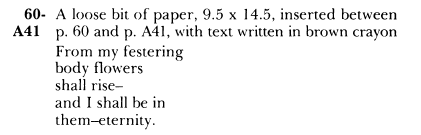

We can see the obvious paraphrasing – rotting body, flowers, eternity – so it’s a matter of which quote came first, as Woll quotes an 1892 note. Then Woll directs us to see the “small card placed in the volume”, so I look this up by going to the final section of the book, “Tree of Knowledge: Catalogue & Translation”. This section is a painstakingly recreated transcription/description of the contents of Munch’s portfolio/scrapbook, seeking a chronological order of all his creations; the pages are indicated with numbers and the loosely inserted sheets with letters and numbers. It was translated from Norwegian into English by Alf Bøe, with the advice of James Edmondston, the British Council Representative in Norway.

And in this portfolio, between page 60 and sheet A41, we find the following:

Reference 60-A41 in Edvard Munch: Symbols and Images

It reads:

60-A41 – A loose bit of paper, 9.5 x 14.5, inserted between p. 60 and p. A41, with text written in brown crayon

From my festering

body flowers shall rise-

and I shall be in

them-eternity.

Unbelievable. I am truly speechless as I find this, as I was on the verge of rage-quitting and leaving this stupid hunt alone, and yet… here it is. There is no date, like many of the other scrap papers in the catalog, but I would wager a guess between 1890 and 1910, judging by the dated papers in the same catalog. It also matches with the timeline of the 1892 note. Perhaps Munch went on this walk and found comfort in the idea of becoming one with nature – “to pass into, be united with” – and scribbled his thoughts in a few words, in brown crayon, on a loose piece of paper that would have become lost among all his other thousands of loose pieces of paper. Four verses, and nothing more. Do I feel cheated? Does knowing the context cheapen – or enhance – its meaning?

To get a better idea of the context, I read Woll’s entire article. I learn that upon Munch’s death, he bequeathed his creations to the City of Oslo, which also included drafts, memoranda, paintings in thousands variations, and papers upon papers upon papers – with many lacking any recognisable dating. Munch himself tried to organise his works and notes into a more digestible format, the Tree portfolio being one of many attempts to create a logical format – but what logic is there to art, in the end? Thousands of notes, loose papers, poetry scribbled in crayon, sketches and drafts, woodcuts and paintings, all stapled and glued and sewn together. It is reported that he had a lot of difficulties trying to piece them in a coherent manner, and he died before it was ever completed. On a deep level I understand the need, the drive to try to catalog everything and anything about your soul in neat squares, folded and exposed on request, but it’s a Sisyphean task to believe that logic would add much value to the art.

Still he tried. Woll writes that Munch likely meant for a logical structure, as some pages feature headings such as “Childhood”, “Philosophy”, “Art”, to the more introspective “Mental State”, “Moods” and “Death” (which – very relatable). The title comes not from a phrase written on the cover of the portfolio, but from a title page left within the loose pages with a crayon sketch of the tree from the biblical myth – and so the archivists named it after this.

Later in Woll’s essay, Munch says something else that sticks out in my mind.

Page 238 in Edvard Munch: Symbols and Images

It reads:

The belief that he was “cursed” with undesirable inherited traits created conflicts in his relations with other people. But the key to much of Munch’s art is to be found in the reflections he made on his fate. In a note he said:

A German asked me : but you can get rid of many of your afflictions. Then I answered – they belong to me and my art – they have become one with me and it will ruin my art. I want to keep these sufferings. (OKK T 2784b)

This idea of being ruined by affliction – consumption, as it was more commonly known – and also being possessive of your suffering is a reoccurring theme for other artists of that era, but I am really touched by the palpable suffering of Munch’s pieces. The theme of “body rotting” – it has its allure, either from a biblical perspective (you come from dust and you will return to dust), but more poignantly, from an introspective view.

You might have noticed that artists (the writers, the painters, the auteurs, whatever form they choose to express their concealed colours with) don’t particularly like themselves, once you get past the false veneer of arrogance and egotism. Whether made insignificant by a lackluster society, being penniless, or sickness and heartbreak and rot, it’s no wonder there are so many metaphors of death and illness.

I am going to pause here to touch on a yet unmentioned aspect of inspirational quotes.

There’s a good reason why there are so many quote-centered websites , set up with an emphasis on social media sharing rather than the source or origin. It’s because this is a form of media where the author isn’t the most important puzzle piece – but the reader. You, the reader, will come upon a quote that will speak to your particular poison of creativity (Ray Bradbury’s “You must stay drunk on writing so reality cannot destroy you”1), your twisted views of romance (Andre Breton’s “My wish is that you may be loved to the point of madness”2) or a shattered sense of self (Franz Kafka’s “I usually solve problems by letting them devour me”3). You will project your dreams and traumas and inadequacies into a dead stranger’s mouth, because if we couldn’t carry our dead within us, we’d be empty. And so, in my quest to hunt down the quote4 to its source I psycho-analyse my own biases – my tendency to over-romanticise and over-simplify – and I learn a little bit more about yourself.

A tree (of life) growing out of a grave at Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris, France

In context, Munch’s “rotting body” brings to air his desire for his legacy to continue after his death, for him to continue living in his art.

In projection, the rotting body is more than carnal putrefaction – it is the self, the rot of the soul, brought upon uncontrollable circumstances of one’s life; bitterness has started marring your relations, your experiences. The rot might well be inherited trauma, since so many parents excel in breaking their children from birth, and so those children carry that rot with them until they become adults, and can then pass it on to their own lovers and families and children.

But what happens when flowers grow out of rot? It’s life out of death, rebirth and transformation, a hand reaching out. It’s not refusing to accept the rot, because some of us were born rotten and it’s hard to learn to fight what comes from within, and the only way to win, is… well. For flowers to grow from the sick; to plant tiny seeds of colour into a barren land, to wrench a flicker of flame from the driest of landscapes.

It is a revolutionary act to look at the ugliness festering within you and decide to grow flowers instead.

- Bradbury, Ray. Zen In The Art Of Writing. Harpervoyager, 2015, Preface: pp. X-XI. (go back up)

- Rosemont, Franklin, and André Breton. André Breton – What Is Surrealism? Selected Writings. Pluto Press Ltd., 1978, pp. 164-168. Also see the post. (go back up)

- Kafka, Franz. Letters To Friends, Family, And Editors. Schocken Books, New York, 1977. From the “To Max Brod [Matliary, June 1921]” letter. (go back up)

- Is hunting down quote origins an exercise in academia citation? Yes, but not only. (And were these foonotes just me showing off? Also yes.) (go back up)